What Was the Blue in the American Flag Made Of?

The Forgotten Story of Indigo—and What It Still Has to Teach Us

The original American flag's blue came from natural indigo plants, not synthetic chemicals. This living dye helped fund the Revolution and carries profound lessons about materials, meaning, and what we choose to make our symbols from.

The Blue That Helped Build a Nation

We all recognize the American flag: red, white, and blue. It waves on porches, flies at parades, and marks moments of pride and remembrance.

But few ask: What was the blue made of? And even fewer: What does that blue actually mean?

Today, the flag is often polyester—mass-produced, dyed with synthetic chemicals made from fossil fuels. Materials pulled from deep underground, processed in distant facilities, and destined to linger in landfills long after their meaning has faded.

But the original flag? It was something different entirely. It was made from the soil. From plants. From materials that would one day return to the earth.

Indigo: A Plant, A Symbol, A Currency

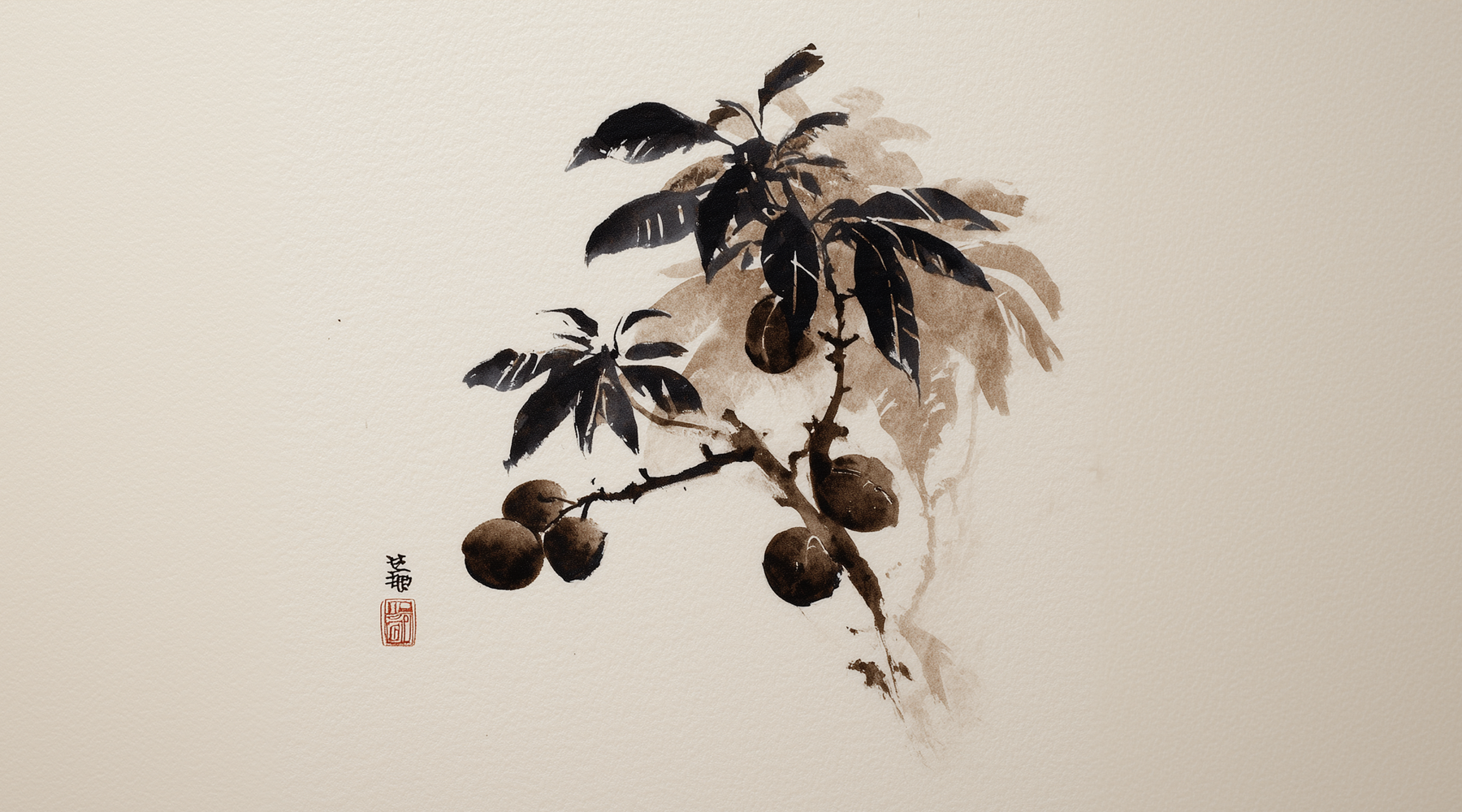

In early America, blue wasn't conjured with chemistry. It came from the Indigofera tinctoria plant—deep green leaves that, through a precise and patient process, released a blue so vivid it was nicknamed "blue gold."

In the 1740s, Eliza Pinckney, just 17 years old, transformed indigo into a profitable crop in South Carolina. Within a few decades, it became a cornerstone of the colonial economy.

By 1776, as the Revolution strained every colonial resource, Benjamin Franklin sailed to France to secure financial aid. Among the goods he brought to prove America's value? 35 barrels of indigo. Blue dye—made from a plant—helped buy freedom.

The Philosophy in the Fiber

There's something poetic—maybe even sacred—about a symbol of liberty being made from something that grows.

Indigo was once farmed, fermented, and applied by hand. It came from the land. It served its purpose. And in time, it broke down—back into the soil, part of the cycle.

Today, most materials are engineered to resist that cycle. We've built a world where things don't return, don't decompose, don't belong anywhere when their use is done. Flags, clothes, banners—symbols—have become objects without endings.

We forget that even ideals must be held in material form. And those materials speak.

Materials Have Memory

The story of indigo is beautiful—but complex. It speaks of ingenuity, resilience, and global exchange. But also of forced labor, colonialism, and extraction.

Just as cotton holds the story of slavery, indigo holds its own contradictions: healing and harm, medicine and exploitation, value and violence.

To reflect on the materials of the flag is to reflect on what we choose to remember, and what we choose to overlook.

A flag is not just color. It is meaning, made physical. And what we make it from says as much as what it stands for.

What Was the Original Blue in the American Flag?

- ✅ Made from natural indigo dye

- ✅ Cultivated by Eliza Pinckney in the American South

- ✅ Used by Benjamin Franklin to secure funding for the Revolution

- ❌ Not plastic. ❌ Not petrochemical. ❌ Not permanent

AIZOME: A Return to Soil-Based Beauty

At AIZOME, we work with these same plants—indigo, madder, cotton—not just to revive tradition, but to heal from it.

Our AIZOME ULTRA dyeing method uses only plants, water, and ultrasound—no synthetic chemicals. No residues. No toxins. Just textiles that begin in the soil, nourish your skin, and can one day return to where they came from.

This isn't just about sustainability. It's about reverence. For the land. For the past. For what we make—and what it makes of us.

A Final Reflection

Beneath the surface of every flag—every stitch, every thread—is a deeper story. One of material, of method, of meaning.

There was a time when all human creation began and ended in the soil. A time when cloth came from the land just as much as the food we ate or the homes we built.

Cotton would grow, be harvested, spun, and woven. Indigo plants would be fermented to create the deepest blues. And eventually—through wear, time, and the natural rhythms of life—these fabrics would return to where they came from. To dust. To earth.

Today, we make things from substances that resist decay. Made in places we'll never see, from ingredients we don't understand. And when they're finished, they don't return. They stay. Symbols without decomposition. Objects without closure.

The flag is a powerful symbol of ideals. But it is also a material thing. And to think about its material is to ask: What do we want our freedom to be made of?

If it cannot one day become soil again, should we really be calling it ours?

Bedding

Bedding

Clothing & Accessories

Clothing & Accessories

Artisan Line

Artisan Line

1 comment

George T.

This piece really moved me. I had no idea the original blue of the American flag came from indigo plants, something alive, grown, and meaningful. The contrast between that and today’s plastic-based flags is striking. It’s a powerful reminder that even the materials we use carry messages, and that honoring symbols also means honoring their origins. I already love AIZOME for your commitment to soil-based, regenerative textiles, but this deeper historical lens adds a whole new layer of appreciation.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.