Japanese ukiyo-e maestro Hiroshige's woodblock print, Wakamurasaki, shows a young Prince Genji getting a first glimpse of lady Murasaki in an illustration from Murasaki Shikibu's, The Tale of Genji, considered by many to be the world's first novel.

Court life in the Heian period (794-1185), where the story takes place, was characterized by gaudy kimonos in vivid colors, but Genji's in Wakamurasaki stands out as it is a more subtle dark blue with a white squared pattern. It is actually one of the first glimpses into indigo-dyeing in Japan, or aizome (藍染) as it is termed, from the Japanese words for indigo (ai) and to dye (someru).

Indigo is the oldest plant dye known to man, used for thousands of years in places such as ancient Egypt, where mummified remains have been discovered wrapped in indigo-dyed cloths. It entered Japan through the Silk Road around the 8th or 9th century, and as with so many other things, it soon took on its own unique Japanese touch. As a matter of fact, when British chemist, R.W. Atkinson, visited Japan in 1874, he saw so many indigo-dyed fabrics, even among commoners, that he labeled the color "Japan Blue".

"Indigo entered Japan through the Silk Road around the 8th or 9th century, and as with so many other things it soon took on its own unique Japanese touch."

Japan Blue

Samurai wearing aizome

The third and final stage of the evolution took place during the Edo period (1600-1868). This was when aizome became public, so to speak. Commoners were prohibited by the Shogun from wearing too explicit colors, limiting their choice of wardrobe to subdued colors such as blue, brown or grey. This didn't stop them from using their creativity, as indigo-dyed fabric provided an excellent opportunity to express one's individuality and fashion due to its unique pattern-making (more on that here). Cotton and hemp also proved relatively easy to dye with indigo, and only noblemen were allowed to wear silk.

Soon, Japan exploded in a spectrum of indigo, as everyone from merchants to farmers - who, like the aforementioned samurai found many practical uses in aizome's medicinal (and insect-repelling) properties - started donning aizome wear in their daily lives. Shops followed suit and dyed their noren curtains indigo, and perhaps most relevant for you reading this right now, people started sleeping on indigo-dyed bed sheets. No wonder R.W. Atkinson labeled indigo Japan Blue as it must have been literally all around him.

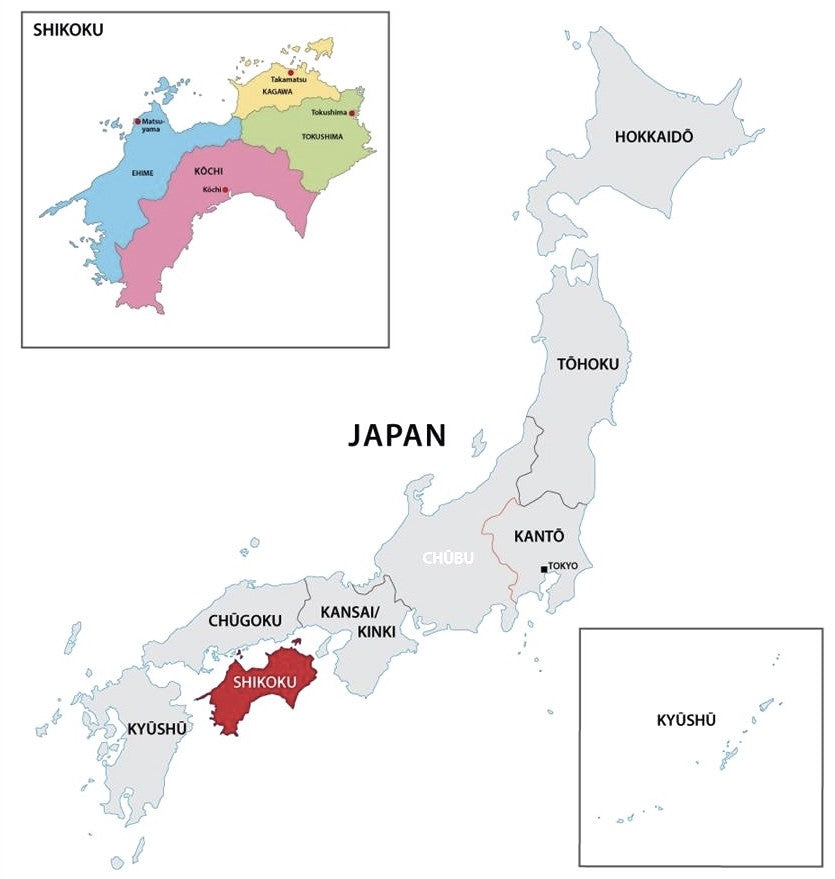

Shikoku, the home of Aizome

Aizome production thrived along the Yoshino river in Takamatsu, Shikoku, long the Mecca of indigo-dyeing in Japan. As the river often overflowed, rich silt spilled into the nearby fields, making them much more suitable for indigo than rice farming. Artisans grew by the number and perfected their skills for centuries until industrial production took over, making way for harmful but much cheaper synthetic indigo. Today, Shikoku remains the nexus of natural indigo production, but very few artisans still ply their trade. However, with more and more scientific reports confirming the medical benefits of natural indigo, we're standing at the dawn of a second coming of aizome.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dan Asenlund is a writer and filmmaker dividing his time between Tokyo, Japan and Stockholm, Sweden. His travel writing has appeared in The Japan Times, his explorations of fringe Japanese culture in Metropolis Magazine and his fiction in Eastlit Journal. His short film, Four Degrees of Jonas Rydell, was screened at festivals across Asia and he is also a Student Emmy-nominated documentarian from his days at the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication.

Image: Avue Copyright, used by permission.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.